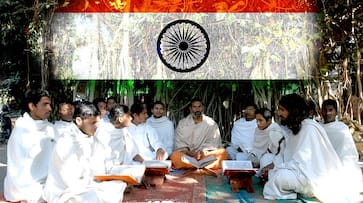

A resurgent India requires a new diplomatic image of India as its own civilisational centre, notably its role in the Indo-Pacific region — not just reacting to political currents from the outside, but developing both India’s soft power and hard power

India, after more than 70 years of its Independence, is still struggling to come to terms with its past, which continues to inhibit its growth and development on many levels. Recognising the value of its older, dharmic civilisation can lead it to a wiser and and more prosperous future.

The partition of India in 1947, which followed the British colonial domination of India’s institutions, cast a long shadow over the country, which has yet to be removed. India gained political freedom but its intellectual freedom was not won along with it. Instead of developing a robust new Indic school of thought, independent India fell into the quagmire of Marxist dialectics and dynastic sycophancy. Its intellectuals continued to look at the country with an alien vision and disregard for its venerable ancient traditions, which were dismissed on political grounds, not deeply studied, much less looked up to for guidance. While Yoga and Vedanta influenced the West and provided a futuristic vision to humanity, India’s intellectuals treated these profound teachings with disdain.

The partition of India in 1947, which followed the British colonial domination of India’s institutions, cast a long shadow over the country, which has yet to be removed. India gained political freedom but its intellectual freedom was not won along with it. Instead of developing a robust new Indic school of thought, independent India fell into the quagmire of Marxist dialectics and dynastic sycophancy. Its intellectuals continued to look at the country with an alien vision and disregard for its venerable ancient traditions, which were dismissed on political grounds, not deeply studied, much less looked up to for guidance. While Yoga and Vedanta influenced the West and provided a futuristic vision to humanity, India’s intellectuals treated these profound teachings with disdain.

Narendra Modi’s victory in 2014 brought about a resurgence of India’s civilisational heritage of traditional India/Bharata, linking India’s great past with the present as a creative force to mould a more expansive future. Yet the very possibility of this resurgence has caused Modi’s opposition to panic and stonewall any efforts to take the vision of India out of the Nehruvian mould that gave little credence to the powerful civilisation of the country. Any attempt to honour India’s Vedic heritage or Hindu cultural achievements has been opposed as a dangerous majoritarianism, unfit for modern India that was supposed to have no traditional national identity that any group might object to.

The next election in 2019 will mark a decisive phase of this ongoing battle for the idea of India, determining the intellectual currents and civilisational values that will guide the country and underscore its message to the world. Will India have its own civilisational and cultural vision, rooted in its profound dharmic traditions, or will it continue to deny the very basis of its identity and creativity? Will its political and intellectual elite remain suspicious of India’s magnificent past and try to prevent its future from being connected to it, like cutting off a tree from its roots?

Will eternal Bharata fully awaken and displace the Nehruvian idea of India and its apologetic image of the country and its culture? This certainly can be the case, but requires the ascendancy of new intellectual class to make it into a reality. Such a new dharmic intellectual voice is arising, but needs strength and support to reach the echelons of power at media and academic levels that have long excluded its participation.

The following important factors deserve proper consideration for India to arise again.

India needs a new presentation of its history that honours India as one of the main civilisational centres of the world since the dawn of history, not merely a footnote to western civilisation. This includes the role of India’s culture, sciences, and yogic spirituality in influencing the world, as far as China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia, and Indochina to the east, extending west to Central Asia, Iran and Europe.

There must be a new emphasis on the historical continuity of India culturally and politically. Though India did come under foreign rule, its people bravely resisted the massive efforts to replace India’s culture with cultures from the outside that refused to recognise its value. Many great gurus and yogic movements supported India’s dharmic culture through the perilous periods of foreign rule, challenging it at spiritual and intellectual levels. Many native kingdoms opposed foreign rule and maintained their own institutions.

This examination of the past requires a new evaluation of India’s Independence Movement in light of the inspiration it derived from India’s older traditions, including the Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, Yoga and Vedanta, emphasising such towering figures as Swami Vivekananda, Swami Rama Tirtha, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Lokmanya Tilak, Sister Nivedita, and Sri Aurobindo.

Yet linking to the past only has value in projecting a more glorious future. For this an important component is promoting India’s traditional knowledge systems in the country and globally, including Yoga, Ayurveda, Vedanta, Sanskrit, and all dharmic traditions, along with their connections with modern science, medicine, psychology and philosophy. India’s vast art and culture should also be developed, sharing its extraordinary heritage of music, dance, temples and festivals with a new global audience.

Such a resurgent India requires a new diplomatic image of India as its own civilisational centre, notably its role in the Indo-Pacific region — not just reacting to political currents from the outside, but developing both India’s soft power and hard power.

Narendra Modi has helped set the forces in motion for such a new birth of India at a civilisational level to complement its new strength at economic and diplomatic levels. Will that vision continue to prosper or will the old dynastic and Marxist shadows continue to cloud the future? This is the choice for India to make in 2019.

Last Updated Sep 9, 2018, 9:57 AM IST

![Salman Khan sets stage on fire for Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding festivities [WATCH] ATG](https://static-gi.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1hh8y86gvb4kbqgnyhc0w0/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-12-24-37-pm_100x60xt.jpg)

![Pregnant Deepika Padukone dances with Ranveer Singh at Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding bash [WATCH] ATG](https://static-gi.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1ffyd3nzqzgm6ba0k87vr8/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-11-45-35-am_100x60xt.jpg)