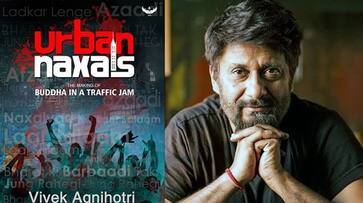

Vivek Agnihotri's exposition on Marxists, Maoists and other leftists, who wish to disintegrate India, comes in the form of a book that narrates the trials and tribulations of the maker of the film, Buddha in a Traffic Jam. In the process, the author of Urban Naxals... lays bare the machinations of the communist gang.

India is an old land, a punya bhoomi, where sages have discovered the ultimate truths and warned us of the traps we fall into in life. But India is also a land ravaged by predatory ideologies that masquerade as compassionate religions, and totalitarian philosophies in bed with those predatory religions that seek to break India and usher in the “end of the world”.

We have industrialists these days, like the old feudal kings, who splurge hundreds of millions on weddings and celebrations even as thousands go begging on the streets outside, dying of malnutrition, and scavenging for food in dustbins. Excess and wantonness live next door to famine and want. From some of the most learned of sages and gurus discoursing on the deepest of human quests to boorish, thuggish politicians holding forth on what they and their ilk are entitled to, in India it is possible to see them all by some channel surfing.

In this land, aspiring young men and women, eager to contribute to the wealth and well-being of the nation, must wend their way carefully among the many others who wish to undermine society, and rob the country of its wealth — both material and spiritual. Among the latter are what Rajiv Malhotra and Aravindan Neelakandan have called the “breaking India” forces, trained and armed by Marxist-Maoist combines, who have, over decades, infiltrated every government agency and institution, and whose writ runs in wide swathes of the country.

The title of Vivek Agnihotri’s book, Urban Naxals: The Making of ‘Buddha in a Traffic Jam’, does not fully capture the ambit of the book as the author writes not just about the making of the film. It’s also about what he went through while trying to get the film released in theatres across the country — failing at it first, screening it on nearly 50 university/college campuses. The final push that got the film across the many barriers laid by feckless producers and distributors, and the furore over and the backlash to — as well as the heady reception of — the movie is what constitutes the book.

Urban Naxals… is a book that looks India and Indians in the eye, celebrates those facets of the land and the people who have made it a destination for insight, spiritual succour, and celebration, as well as cries in horror and anger at the chaos, the indiscipline, the poverty and the filth. It is about a system that has been leveraged by destructive forces intent on breaking India into a million pieces, feasting on every bit and the crumbs left thereafter.

Agnihotri tells us, without frills and unnecessary theorising, the reasons for the utter silence of India’s mainstream media and intelligentsia in response to his stylish and powerful movie that narrates the tale of a naxal activist who is also an academic, teaching at a prestigious business school, and who is complicit in the grand scheme to destroy the country. Agnihotri is not just a fine filmmaker/director but also a talented writer, who brings to life the challenging, testing quest to tell the story of the nexus between violence-advocating activists masquerading as academics, NGOs and their tie-up with naxals and “break India” forces, and the Maoists’ quest for power and control by keeping India and its most neglected and downtrodden hungry and distraught, and under their bloody foot.

Agnihotri tells us that, after a couple of successful films, Chocolate, and Goal, he is ready to make another one, ramp up his Bollywood credentials, get the deep money bags to invest in his ventures of storytelling, and get Indian viewers a more thoughtful and attractive fare. What then happens, and how he cobbles together a group of the uncommon, atypical, and non-traditional, and therefore “accidental” producers and backers of a film on “intellectual terrorism,” is a captivating aspect of this book.

From the setting at the swank Indian School of Business, where a small group of students are interested in making a short film as part of their business school project, Agnihotri takes on the journey of how the film got made: getting a big film made on little money; the feverish hunt for actors, crew, and technical and artistic talent; inspired breaks, gut-wrenching disappointment, twists and turns that not even a talented script-writer could have imagined. All of this Agnihotri captures in this fascinating book.

One hopes that Agnihotri would be writing and directing a movie based on those experiences, for all of Bollywood’s insider machinations, the preening of stars, and the chicanery and foolhardiness of producers would make for an interesting tell-all.

The book can be read in one sitting, even if it is a nearly 400-page opus. If such a book can be read in one sitting, you would not be wrong in thinking that it must a gripping crime-thriller, or a seductive title like Fifty Shades of Grey. There is a little sex and a lot of crime in the movie, but what we find in this beautifully recounted first-person narrative is a story about the idea of a film, the making of it, the screening of it in on college campuses, and finally the begrudging acknowledgement by some of the scheming/manipulative political activists and politicians of the importance of Agnihotri’s film.

My reading of this book was a little quirky. I had read reports about Agnihotri being heckled, ambushed, and attacked at the once famous and now infamous Jadavpur University, where “student” activists broke his arm, injured his shoulder. If not for the quick thinking by his driver, he would have easily become another victim of a communist/naxal public lynching by those who reside at the university claiming they are students. The chapter on his visit to the Jadavpur University is the penultimate chapter in the book. It is a frightening account of how a university has been converted into a gulag-like camp with leftist/Marxist students and their ideological mentors having taken over the campus, and anyone not toeing their line is considered a heretic and an enemy.

The build-up of events leading to the screening of the film on a white bedsheet out in the open, as the university authorities had colluded to stop those students who were in favour of screening the film in an university auditorium, is straight out of a crime-thriller and Agnihotri, a master raconteur, tells the shameful tale of a university that has been turned into a rotten political establishment, whose violent-anarchist denizens are ready to rampage the land in their bid to destroy their ascribed “class” enemies. In this chapter, we read how “freedom of expression” is a slogan of the “left/liberal” for selective application and for the license to shut down voices of opposition.

There are three parts to Vivek’s book, as Abhinav Agarwal deftly summarises in his review of the book. The first part includes snippets recounting his growing up in Bhopal, his journey as a filmmaker, and the challenges and breakthroughs in making a film. The second part focuses on the Marxist/Maoist/naxal menace that has led to bloody murders and mayhem in “red corridors” across the country, and which has wormed its way into urban India. From the media houses to filmdom, from government offices to the police forces, and insidiously, dangerously indoctrinating students on university campuses into this violent Maoist ideology where “revolution” demands the scalp of millions! Think Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot, and the third part is the story of Agnihotri’s determination to have Buddha in a Traffic Jam screened at university campuses across the country from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) to Jadavpur University, from IIT Chennai to The National Academy for Legal studies and Research (NALSAR), and from Allahabad University to Benares Hindu University, and from Osmania University to the Indian Institute of Science.

The last part makes for some really dismaying and unnerving reading, and one has to salute Agnihotri for his bravery and courage in facing hostile crowds of students and their manipulative mentors, some of whom came up to him while he was speaking — to literally twist his arm and beat him up! This is what so many of India’s universities have been converted into: mediocre institutions that have become the hotbed of anarchist, Marxist, caste, and communal politics with thugs masquerading as students, and activists masquerading as teachers. What is deeply disturbing is how many of the once top technological and scientific institutions have been taken over by left-leaning humanities and social sciences faculty (products of JNU and Jadavpur) who now rule the roost, offering a variety of programmes and courses which are merely labs for manufacturing dissent.

The book is divided into four sections: “Buddha is Born,” “In Search of Buddha,” “The Making of Buddha,” and “The Struggle of Buddha”. Agnihotri’s masterly telling of stories, recounting of vignettes, mini-journeys into reminiscences, are what leads the reader through the thicket of modern Indian politics, societal dynamics, and the control and capture processes in the film industry and in education.

A fine foreword by Prof Makarand Paranjape, who taught English at JNU, and who himself was the target of leftist/Marxist colleagues and their student armies, sets the tone for the book: “A traffic jam is the worst possible situation to be if you want to get to some place on time. But if you discover your Buddhahood right in the middle of the impasse, it’s a miraculous way of beating the odds of life,” he writes, giving a clue to the title of Agnihotri’s film. More importantly, Prof Paranjape notes this of Agnihotri’s life and writing: “It is a thinking woman’s and man’s book. It is also brimming with compassion, consideration, and passionate concern for our poor, ‘suffering, conflicted, mediocre India’.”

“Read the book… because some people don’t want you to,” writes Rahul Roushan, in a blurb adorning the cover of the book. Yes, read the book, buy a few copies of it and give it to your friends and family members. The matter is urgent, and it is a matter of life and integrity, of the worth and weight of an ancient civilization and the viability and endurance of a modern nation buffeted by inimical forces.

Except for a couple of major English language newspapers (The New Indian Express), (Free Press Journal), no other newspaper or magazine has published a review of this important book. Whereas, in late August, early September, there was a rash of op-eds, commentaries, tweets, and challenges, when Agnihotri gave a call to identify those people who have been at the forefront of the naxal movement. That is the power of the “establishment,” even as it undermines the country it prospers in.

Ramesh Rao teaches communication at Columbus State University in Columbus, Georgia, the United States. He has taught in the US for more than three decades. He is the co-author of a book on intercultural communication and author of a handful of books on Indian politics and society.

Last Updated Dec 27, 2018, 6:20 PM IST

![Salman Khan sets stage on fire for Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding festivities [WATCH] ATG](https://static-gi.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1hh8y86gvb4kbqgnyhc0w0/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-12-24-37-pm_100x60xt.jpg)

![Pregnant Deepika Padukone dances with Ranveer Singh at Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding bash [WATCH] ATG](https://static-gi.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1ffyd3nzqzgm6ba0k87vr8/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-11-45-35-am_100x60xt.jpg)